The rituals performed at birth suggest that in the Naxi traditional thought the entering of the Sv life god in a person is a gradual process developed during the last term of pregnancy and the first days of life, and that this process is considered complete in a first phase, when the new born is one month old[1]. Before this time, lacking the protection of the Sv life god, mother and child, considered especially vulnerable, are carefully protected and object of some taboos, with the mother usually fed with chicken soup and eggs, not being allowed to bathe or wash her hair, nor to go out of her courtyard (Pinso 2006: 150).

In Baidi, where the traditions are better preserved, when a woman gets pregnant she avoids those tasks requiring more physical effort. As she is considered unclean, she must observe different taboos. In the time of delivery she is assisted by the two future grandmothers who would take the newborn once he is born, cut the umbilical cord with scissors, and wrap his belly with a cotton cloth. The placenta is wrapped in vegetal paper and put in a jug, then buried near a tree or in a not much trodden place, with the umbilical end facing up, lest the baby will suffer from nightmares.

If during this process some problems appear, the members of the family will pray to the gods and ancestors to protect mother and child. Three small stones are hung on the main door of the house to let the people know that a child has been born, as nobody can visit this home at night. In some villages the same day of birth a Dongba is called to perform the ritual of getting rid of the dirtiness. To do it, he will carve a horse with wood of black willow and a puppet with eyes, mouth, and nose with a branch of red willow, as well as some magical implements to expel the evil spirits. He will put all these things in a basket near the heaven prop, and will read some chants to purify the house.

The climax of the ceremony is when the Dongba, after sprinkling water on every member of the family, sprinkle some water on the body of a chicken, which is immediately sacrificed, symbolizing that it will take away all the impurities of the family (Yang 2008). It is interesting to remark the presence of the horse both in the first moments of life and in the last ones, and to remember its role as a spiritual carrier in shamanistic religions. In villages around the Lijiang plain the third day after birth a Dongba is invited to worship the God Sanduo with a chicken or a pig for giving a name to the newborn.

The first month of life is a time of important spiritual adjustments, as shown in the tradition that prescribes that until the newborn reaches one month, the members of the family would burn incense and pray the gods and ancestors every day. When he is one month old, the mother would wash her hair and would invite a Dongba to celebrate a simple ceremony of Guide the child to go out, when the Dongba sings his prayers opening the road and the mother follows him with the child at her back. A ceremony with an interesting parallelism with this other performed after death, when the Dongba would open the road again, this time to the ancestors’ realm.

The child must have a needle inserted in his cap and a little sickle hanging from his neck, to avoid the attack of evil spirits. After opening the road they can go back home, where friends and relatives would present the new-born with baba, rice and pork, and the Dongba would choose a name that must be related in a magical way to the age and horoscope of his mother (He Shaoying 2001: 166-170). The fact that the baby isn’t called by his name until he is one month old shows that the Naxi think he is not a person until this age, possibly because this is the time the Sv god needs to enter his body.

Children are usually breastfed until they reach one year old, when their milk is officially stopped, though sometimes it goes on for some months. To stop the baby from drinking milk they have some methods, as separating mother and child during one week, smearing the mother breasts with pork bile, or drawing dreadful designs on the mother’s breast. Then the child is fed three times every day with corn porridge. During the first year of life the babies are not washed (He Shaoying 2001: 166-170).

This fragment is part of Ceinos-Arcones, Pedro. Sons of Heaven, Brothers of Nature – The Naxi of Southwest China.

More posts on China ethnic groups

El suicidio a causa de la venta de esposas en la antigua China

El suicidio a causa de la venta de esposas en la antigua China Durante la dinastía Qing las relaciones familiares fueron una continua causa de suicidios, especialmente para las mujeres. Muchas de las características singulares de los matrimonios chinos llevaron a las...

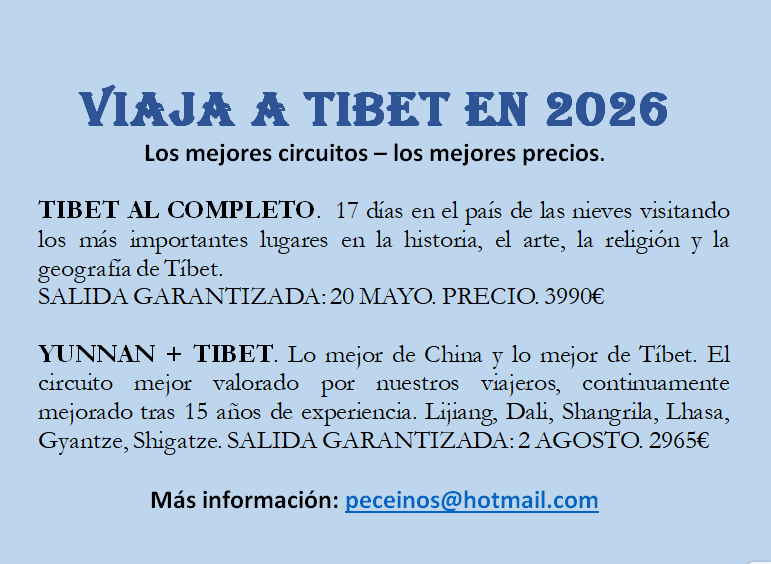

Descubre el tesoro de la montaña Weibaoshan en Yunnan

Descubre el tesoro de la montaña Weibaoshan en Yunnan La montaña Weibao (巍宝山) es una de las montañas sagradas de Yunnan. Reúne en su escasa superficie un conjunto histórico, artístico, natural y monumental que hace de ella un lugar único en China y puede que en el...

Así eran las procesiones imperiales al Templo del Cielo

Así eran las procesiones imperiales al Templo del Cielo. Los que conocen China, aunque sólo sea mediante un viaje rápido y han visitado el Templo del Cielo en Beijing, seguramente se habrán quedado fascinados por la belleza sobria de sus construcciones, pero tanto si...

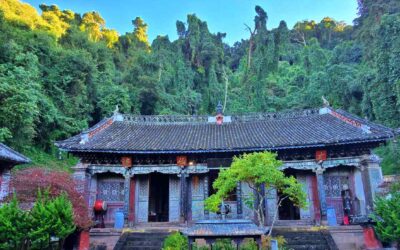

Escenas de la vida del Budha más frecuentes en el arte tibetano

Escenas de la vida del Budha más frecuentes en el arte tibetano En realidad hay unos pocos momentos que se repiten con mucha frecuencia en las pinturas tibetanas, en algunas versiones son 8, número mágico para los tibetanos, que se corresponde con el Óctuple Sendero y...

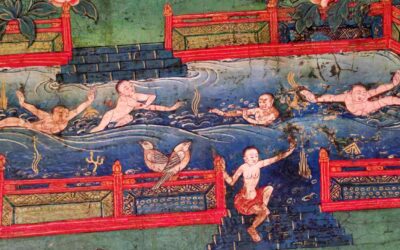

El perro como psicopompo en China

El perro como psicopompo en China Una de las más antiguas creencias humanas fue pensar que tras la muerte había una parte inmaterial de la persona, posteriormente llamada alma o espíritu, que no desaparecía con el cuerpo. Su origen podría deberse a la “presencia” de...

Un ambicioso proyecto para reescribir la historia

Un ambicioso proyecto para reescribir la historia Es lo que encontramos en Lhamsuren Munkh-Erdene, The Nomadic Leviathan. A Critique of the Sinocentric Paradigm. Brill, Leiden, 2023. Actualmente disponible para descarga gratuita en la página web de la editorial. Este...