Pedro Ceinos Arcones. Yu garden in Shanghai: Archetype of Chinese garden. Dancing Dragons Books. 2019.

(Excerpts from the book)

The Yu Garden is Shanghai’s main monument and the one that best summarizes the city’s history over the past few centuries. A private garden typical of southern China, it concentrates the fundamental elements of vernacular gardening in only two hectares, creating a separate space that opens the visitor’s mind and eyes to a hundred landscapes and a thousand scenes. Zigzagging paths, small walls that separate different environments, ponds that extend beyond the reach of view, pavilions that stand on rocks and water, doors with whimsical shapes, etc., every single detail makes the visitor discover a different world with every step they take. The garden is carefully designed and built as a delicate landscape that represents ancient China’s high aesthetic value and its artistic and cultural universe.

Yu Garden is one of the most outstanding private gardens in China and is at the same time a safe haven full of peace and harmony from all the hustle and bustle of modern Shanghai. Some scholars consider it «the most beautiful garden in southern China». In addition to being well known for the subtle planning and harmonious combination of mountains and ponds, its small surface area reflects the characteristics of gardens in the South, with some singularities that relate it to the imperial gardens in the north. Mr. Pan, its creator, had in mind to recreate for his parents the atmosphere of the imperial gardens of the capital, Beijing. This makes it a unique garden in China.

Yu Garden was originally a private garden, with a unique set of pavilions, rocky mountains and ponds. Since its creation, the garden has been the center of Shanghai’s cultural and social life. Its pavilions, halls, towers, bridges, ponds and artificial mountains offer more than 40 famous views or unique landscapes. There is a local saying: «He who comes to Shanghai and does not visit the Yu Garden is as if he had not come at all.» (China 1989).

The Yu Garden in Shanghai has become, through the vicissitudes of history, the universal garden, the archetype of the Chinese garden, and with it, an elegant and refined way of life linked to the aristocratic families of southern China, and to Chinese culture in general. As Kristen Chiem has shown, during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a powerful parallel was established between the Yu Garden and the garden in which the action of the famous novel Dream of the Red Chamber takes place, a highly popular novel in Shanghai of those years. A parallel that included not only the architectural elements and social activities common to the gardens of southern China, but even an analogy between the tragic end of the Pan family (builder of the garden then ruined) and the Jia family (protagonist of the novel that also ends in decadence). This affected the dress code and behavior of numerous ladies and courtesans of the city. The garden thus became the frame where the feminine images of society were constructed. The representations of the conventional beauties in the paintings, as well as those of the characters of popular literature, or the new heroines of urban culture were represented in environments that undoubtedly evoked a Dream of the Red Chamber embodied in the elements of the Yu Garden. As a result of this trend, an illustrated edition of the novel published in Shanghai in 1930 used the iconography of the Yu Garden to represent the garden of the novel.

On the other hand, the main components of the garden, especially the Mid-Lake Pavilion and other elements, also came to the West as a paradigm of Chinese culture. Through their incorporation into the most popular iconographic motif on porcelains exported to Europe and on those manufactured there in the Chinese style: including “a pavilion beside a willow tree, a bridge with three figures, a boat, a main teahouse, two birds, and a fence across the foreground of the garden» (Chiem 2016: 314).The popular use in different cultural environments of the main elements of the garden to portray idealized images of life in China and of a sublimated imperial tradition, responded to the its own characteristics: the splendor of its construction and the desolation of its decadence, its use as part of the City God Temple and its transformation in the commercial, cultural and social heart of Shanghai. As Shanghai became the door of China to the world, the garden represented the orientality of Shanghai, which in turn was the only one open to westerners in China.

That is why natives and foreigners are still attracted to a garden they consider a living representation of the virtues and refinement of an idealized China in the past, and why the Yu Garden is an indispensable element of Chinese Cultural Heritage.

The Yu Garden is the heart of Shanghai, being its most famous monument and the only one that identifies it in the midst of its avant-garde and modernity, with its purely Chinese character. It is the heart of the city, and the umbilical cord that keeps it united with tradition. Located in the center, if not geographical, at least cultural and social of the ancient city, the «Chinese city». It is the most important icon with which visitors and residents identify Shanghai. The Yu Garden and its surrounding monuments are the dream of the past, of an undefined cultural sophistication that materializes nevertheless with a careful harmony and shocking beauty. They are the embodiment of a city’s glorious past.

According to Chinese tradition, a visit to a garden is not a passive activity. As in any appreciation of a work of art «the visitor is expected to enter the garden not only physically, but also intellectually and emotionally» (Bryant 2016). In order to turn the visit to the garden into an emotional experience, the visitor will have to know, at least in part, the cultural environment in which the garden was built and the way in which its elements were organized, and ultimately learn the rudiments of the language spoken in the garden. A language whose basic signs we will introduce throughout this work.

More posts on Chinese culture

El suicidio a causa de la venta de esposas en la antigua China

El suicidio a causa de la venta de esposas en la antigua China Durante la dinastía Qing las relaciones familiares fueron una continua causa de suicidios, especialmente para las mujeres. Muchas de las características singulares de los matrimonios chinos llevaron a las...

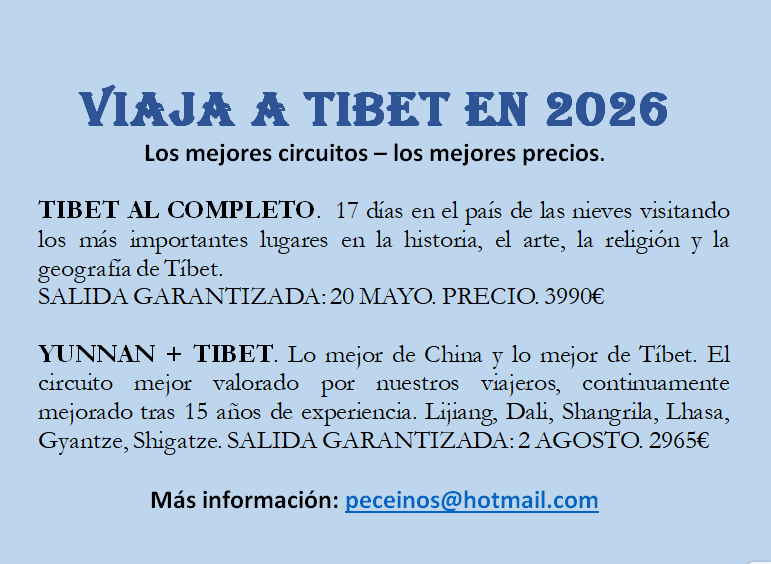

Descubre el tesoro de la montaña Weibaoshan en Yunnan

Descubre el tesoro de la montaña Weibaoshan en Yunnan La montaña Weibao (巍宝山) es una de las montañas sagradas de Yunnan. Reúne en su escasa superficie un conjunto histórico, artístico, natural y monumental que hace de ella un lugar único en China y puede que en el...

Así eran las procesiones imperiales al Templo del Cielo

Así eran las procesiones imperiales al Templo del Cielo. Los que conocen China, aunque sólo sea mediante un viaje rápido y han visitado el Templo del Cielo en Beijing, seguramente se habrán quedado fascinados por la belleza sobria de sus construcciones, pero tanto si...

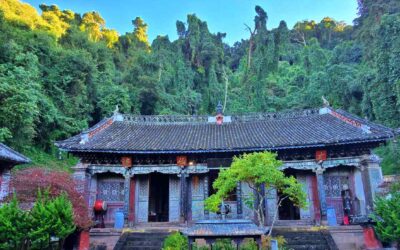

Escenas de la vida del Budha más frecuentes en el arte tibetano

Escenas de la vida del Budha más frecuentes en el arte tibetano En realidad hay unos pocos momentos que se repiten con mucha frecuencia en las pinturas tibetanas, en algunas versiones son 8, número mágico para los tibetanos, que se corresponde con el Óctuple Sendero y...

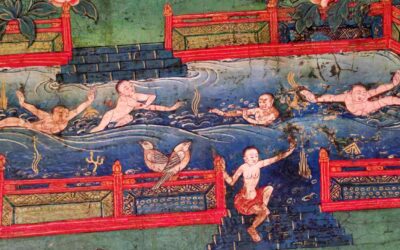

El perro como psicopompo en China

El perro como psicopompo en China Una de las más antiguas creencias humanas fue pensar que tras la muerte había una parte inmaterial de la persona, posteriormente llamada alma o espíritu, que no desaparecía con el cuerpo. Su origen podría deberse a la “presencia” de...

Un ambicioso proyecto para reescribir la historia

Un ambicioso proyecto para reescribir la historia Es lo que encontramos en Lhamsuren Munkh-Erdene, The Nomadic Leviathan. A Critique of the Sinocentric Paradigm. Brill, Leiden, 2023. Actualmente disponible para descarga gratuita en la página web de la editorial. Este...

More posts on China ethnic groups

El suicidio a causa de la venta de esposas en la antigua China

El suicidio a causa de la venta de esposas en la antigua China Durante la dinastía Qing las relaciones familiares fueron una continua causa de suicidios, especialmente para las mujeres. Muchas de las características singulares de los matrimonios chinos llevaron a las...

Descubre el tesoro de la montaña Weibaoshan en Yunnan

Descubre el tesoro de la montaña Weibaoshan en Yunnan La montaña Weibao (巍宝山) es una de las montañas sagradas de Yunnan. Reúne en su escasa superficie un conjunto histórico, artístico, natural y monumental que hace de ella un lugar único en China y puede que en el...

Así eran las procesiones imperiales al Templo del Cielo

Así eran las procesiones imperiales al Templo del Cielo. Los que conocen China, aunque sólo sea mediante un viaje rápido y han visitado el Templo del Cielo en Beijing, seguramente se habrán quedado fascinados por la belleza sobria de sus construcciones, pero tanto si...

Escenas de la vida del Budha más frecuentes en el arte tibetano

Escenas de la vida del Budha más frecuentes en el arte tibetano En realidad hay unos pocos momentos que se repiten con mucha frecuencia en las pinturas tibetanas, en algunas versiones son 8, número mágico para los tibetanos, que se corresponde con el Óctuple Sendero y...

El perro como psicopompo en China

El perro como psicopompo en China Una de las más antiguas creencias humanas fue pensar que tras la muerte había una parte inmaterial de la persona, posteriormente llamada alma o espíritu, que no desaparecía con el cuerpo. Su origen podría deberse a la “presencia” de...

Un ambicioso proyecto para reescribir la historia

Un ambicioso proyecto para reescribir la historia Es lo que encontramos en Lhamsuren Munkh-Erdene, The Nomadic Leviathan. A Critique of the Sinocentric Paradigm. Brill, Leiden, 2023. Actualmente disponible para descarga gratuita en la página web de la editorial. Este...