Pedro Ceinos-Arcones. China’s last but one matriarchy: The Jino of Yunnan. 2018

Jinuos’ main religious specialists are bailabao, mopei and zhalai or Blacksmith. The oldest man of the main clan in the village is called zhuoba or mother of the village; the oldest of the second clan is the zhuosheng or father of the village. They have as leader of the village, important ritual functions, presiding over the most important ceremonies and rituals. The oldest woman in the village, called youka, also has some ritual functions. It is possible that in the past most of the clan leaders were women and maybe shamans: the wisest shamans that could divine omens and chant incantations, as they are credited with the first improvements in human civilization.

They believe the power held nowadays by the religious specialists is a heritage of that of the legendary shamanesses, and, as the spiritual power belongs to women, they must feminize themselves. Sometimes when male shamans conduct rituals, they are required to dress as women, or they need to get married symbolically to a goddess.

While the zhuoba and zhuosheng are ritual leaders, bailapao and mopei are associated with shamans. Both bailapao and mopei were hereditary posts (Cheng 1993). Ironsmiths, priests and shamans, due to their dependence on the goddesses, must ritually marry one. From the moment when the love for the goddess is manifested to the time when the ritual wedding is celebrated there are certain steps.

The start is a casual encounter with the goddess who is looking for a representative on earth; usually a strange thing happens that only can be explained for as divine intervention, such as appearing and disappearing of shellfish, which is considered a sign that the goddess of the shellfish is playing with him. Then they ask an old bailapao to divine if the person that suffered this experience has really been before the goddess. To do it he must perform a ceremony for the goddess of shellfish with offerings of pigs and other animals, and must even sacrifice a cow. Before the sacrifice of a cow a very important ceremony is performed, when the old bailapao, before an improvised altar, produces two shellfish enacting the ritual marriage between the new bailapao and the goddess of the shellfish. If the result is positive they must inform the chief of the village, who would advise him about a ritual marriage, in which he would act as witness. Then they must build a house for the bride goddess in the groom’s home, which a size of 30 cm high. Inside it they put a nuptial bed. Then they chose an auspicious date and celebrate the proper wedding, sacrificing a cow. Under the sound of drums and cymbals, the old shaman helps the groom to go near the goddess, doing some magic tricks to make her presence known to everybody. At the end they invite the goddess to go live in the new house, and from then on they consider that this man has two wives: the goddess and his mortal wife.

After this ceremony the old bailapao would instruct the new one during some time until the moment when he can perform ceremonies by himself. Later he will build his own altar to the shellfish goddess, consisting of a wood panel with many shellfish hanging from it, and he would place his divination objects below the altar, and make his ritual dress black color and a ritual cap of the same color, decorated with strips of many colors and with many shellfish hanging. His ritual implements include two ritual swords, a female one used inside the house, and a male one to be used outside, a pole and a paper fan, that are usually kept on the altar (Cheng 1993).

More posts on China ethnic groups

Historia de China

En realidad no existe una historia como tal. Toda historia es continuamente reinterpretada a la luz de las ideas preponderantes en el momento de la interpretación. De tal forma que la historia en general y la historia de China que nos concierne aquí, se convierte en...

¿Quieres saber cómo el opio destrozó China? Aquí lo contamos

En realidad lo cuenta el misionero M. Pourias en el Yunnan del Siglo XIX. Hace un tiempo ya comentamos los recientes trabajos de Frank Dikotter y Zheng Yangwen que presentan una visión del opio como una droga no tan fuerte ni tan peligrosa como consideraban los...

El opio en China: mito y realidad

El opio en China es el gran demonio, el causante de la decadencia nacional de la segunda mitad del siglo XIX y el siglo XX, símbolo de la dominación imperialista, y de una China débil, humillada y derrotada por otros países. El opio es a la vez el símbolo de la...

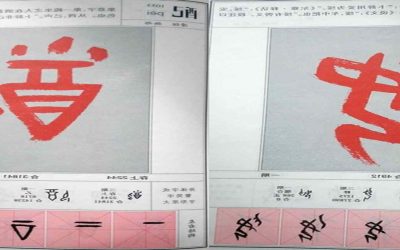

Diccionario de caligrafía de la escritura oracular

Ma Rushen. Diccionario de caligrafía de los Caracteres oraculares. Ediciones de la Universidad de Shanghai. 2012 Fruto de los largos años de dedicación del autor al estudio de los caracteres oraculares y la etimología de los caracteres chinos es este bello libro. Ma...

Sobrevivir al diluvio en el interior de un tambor

La minoría Naxi vive en el Noroeste de Yunnan. Ahora son muy famosos porque la mayoría de los viajes a Yunnan pasan por Lijiang, su hogar ancestral. Su mito fundamental, que se recita cada año cuando rinden homenaje al cielo comienza con la creación del mundo, y...

Los Baiyi de Quzuochong, una comunidad olvidada en el centro de Yunnan

En cualquier país que no fuera China, el descubrimiento en los últimos años del siglo veinte, de un pueblo indígena, formado por apenas 500 personas, diferente de cuantos pueblos le rodean, y que practica una religión única, con una serie de ritos y cultos totalmente...