The origin of Chinese characters in John C. Didier, “In and Outside the Square,” Sino-Platonic Papers, 192, vol. 1 (September, 2009)

- The technology of writing appears suddenly and morphologically fully developed on Shang oracle bones and, later, bronzes at about the same time that wheeled transport was introduced, or c. 1220–1200 BC, and one can only assume that the idea and practice of writing were brought from the settled civilizations of South or Southwest Asia by waves of migrating Iranian Andronovo tribes, though no concrete trace of the spread of writing from the west toward or into Shang China has been discovered.

Although clan or other symbols had appeared previously on Neolithic and Bronze-period artifacts in China, they in no way represent an indigenous development of the full script and syntax that graces Shang bones and, later, bronzes. Nor can they be argued to represent either a language syntax or a set of logographically expressed individual words. They are, in short, simply marks, ones that probably denote the identity or clan / tribe of either the maker of the artifact or its sponsor or owner.

The entire issue of the sudden appearance of the recursively developed Chinese logographic script c. 1200 BC is puzzling, and if, as it seems likely, the idea for and practice of writing were introduced from the West, there must be as yet a — or several — missing link(s) in the record of transmission, since the script(s) that the Iranians could have brought with them would have been consonantary or alphabetical (syllaberial, or uniliterally or phonetically applied), not logographic (see Volume II, Chapter V for a brief discussion of the possible presence in the Shang Sinitic script of a consonantary derived perhaps from the Phoenician consonantary).

Since, when it first appears c. 1200 BC, the Shang, or Sinitic (proto-Chinese), Oracle Bone Script is already fully developed recursively (on the basis of the extensive use of the rebus), some argue that the script must already have been developing in situ in the Yellow River corridor for at least several hundred years or longer. The fact that the script is nowhere evident on any artifacts datable to before the late-13th century BC reflects to many scholars an earlier tendency, for at least several hundred years, to record writing on perishable materials.

According to this thesis, the first evidence of true writing in the Chinese context can be found in graphs [72] expressing only lineage emblems and day-names that were cast on bronzes, occurring at about the same time as and slightly later than the earliest OBIs, in a style that has been theorized to have developed directly from painting characters on perishable materials using brush and ink.

However, such a thesis is wholly conjectural. In a ground-breaking study of inscriptions found on “practice bones” at the late-Shang capital Anyang, recently Adam Smith has demonstrated that scribes at work in the Shang court’s scribal workshops of the 13th and 12th centuries BC, which were essentially diviner-group schools that trained Shang oracle-bone scribes in the preparation of the scripted oracles etched onto turtle plastrons and cattle scapula, most probably were responsible for creating rather rapidly the fully effloresced script that developed at the Shang court for the express purpose of communicating between mostly the Shang king and his ancestors’ spirits using oracle bones.

It may well be, then, that the proto- Chinese Sinitic OBI script, the first script in East Asia, was developed fully artificially to serve the specific and very critical purpose of communication for the sake of obtaining and retaining a religiously based socio-political power. This in turn supports the argument that the idea for and practice of writing were imported sometime during the 15th–13th centuries BC, for it seems that once the Shang Chinese court had been exposed from its contacts with outsiders to the power of the written word, it commanded the creation of a usable script from among the Chinese linguistic and cultural context.

In a mere several generations, it seems, the scribal authorities commissioned with this task succeeded in developing a workable and thoroughly indigenous script, based not only on the idea and practices of writing that had been transmitted from Southwest Asia but also graphically in large part upon a tradition of scratching symbolic clan- or ownership-marking graphs onto various owned artifacts, a tradition that had been practiced in China since Neolithic times.

Therefore, it appears, the first Chinese script, while dependent on the importation from the West of the “technology” of the powerful idea for and practice of writing a language, was developed specifically for the purpose of scratching onto bone with a stiff, sharp stylus characters created momentarily in court educational centers, and not, as it is [73] often argued, from the earlier use of a brush to paint signs on perishable materials (for which absolutely no evidence actually exists). The script seems to have evolved rather lineally and, from a native point of view, indigenously, from the millennia-old habit of employing a stylus to scratch symbols and signs onto items of personal — or personally created — and mostly ceramic objects.

Therefore, although the idea for and practice of enscripting a language appear to have been exogenous, the nature of the first writing in China, using a hard and sharp stylus to etch signs onto bone or other hard but permeable material (typically, pottery), appears to have followed directly from indigenous Neolithic-Bronze period traditions of sign-making on items of personal property to identify origin or ownership. This is not at all to suggest that the Neolithic early Bronze signs constitute any kind of true writing but only that the approach to designing and etching graphs of the OBI script appears to follow from the earlier native — though not at all commonly attested — approach and methods.

More posts on Chinese culture

La Sagrada Montaña Taishan

La Montaña Taishan, la vida y la muerte en la cultura china, según la obra de Edouard Chavannes. Las montañas son, en China, divinidades. Se les considera como potencias naturales que actúan de manera consciente y que pueden, por consiguiente, ser rendidas favorables...

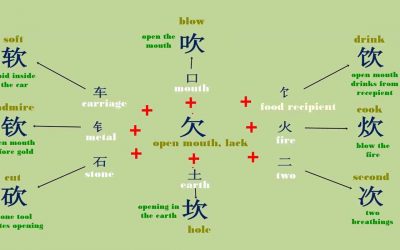

Caratteri cinesi 欠 qiàn – sbadigliare

Caratteri cinesi 欠 qiàn – sbadigliare sbadigliare. dovere a deficiente mancante di HSK - tratti - 4 RADICALe - 欠 La parte superiore si è evoluta dal pittogramma di una bocca aperta. Una 人 persona con la bocca aperta sta sbadigliando, o cercando di evitare la mancanza...

Caratteri cinesi 钦 qīn – ammirare

Caratteri cinesi 钦 qīn – ammirare ammirare rispettare HSK - tratti - 10 RADICALe - 钅 Con la bocca aperta 欠 di fronte ad un oggetto metallico 钅 (jīn fonetico), o d'oro.- 钦慕 qīnmù ammirare Altri post sui caratteri cinesi

Caratteri cinesi 炊 chuī – cucinare

Caratteri cinesi 炊 chuī – cucinare cucinare HSK - tratti - 8 RADICALe - 火 Soffiare 吹 (chui fonetico) sul fuoco huo火 per mescolare e iniziare la cottura.炊具 chuījù utensili da cucina.Altri post sui caratteri cinesi

Family of characters 欠 qian

欠 qiàn – yawn; owe/ short of, lacking. The upper part evolved from the pictogram of an open mouth. A person人with an open mouth is yawning, or trying to compensate for the lack of air. 欠缺 qiànquē – lack/ be deficient of (lack + lack) 欠债 qiànzhài – owe a debt...

Una sesión de exorcismo taoísta

“Mi amigo va a concluir un servicio de exorcismo esta mañana y, si realmente estás tan interesado, espera que puedas venir y presenciarlo." Se detuvo inseguro. “Pero debo advertirte que no es una vista bonita. Realmente es muy desagradable, asquerosa y repugnante.”...

More posts on China ethnic groups

La Sagrada Montaña Taishan

La Montaña Taishan, la vida y la muerte en la cultura china, según la obra de Edouard Chavannes. Las montañas son, en China, divinidades. Se les considera como potencias naturales que actúan de manera consciente y que pueden, por consiguiente, ser rendidas favorables...

Caratteri cinesi 欠 qiàn – sbadigliare

Caratteri cinesi 欠 qiàn – sbadigliare sbadigliare. dovere a deficiente mancante di HSK - tratti - 4 RADICALe - 欠 La parte superiore si è evoluta dal pittogramma di una bocca aperta. Una 人 persona con la bocca aperta sta sbadigliando, o cercando di evitare la mancanza...

Caratteri cinesi 钦 qīn – ammirare

Caratteri cinesi 钦 qīn – ammirare ammirare rispettare HSK - tratti - 10 RADICALe - 钅 Con la bocca aperta 欠 di fronte ad un oggetto metallico 钅 (jīn fonetico), o d'oro.- 钦慕 qīnmù ammirare Altri post sui caratteri cinesi

Caratteri cinesi 炊 chuī – cucinare

Caratteri cinesi 炊 chuī – cucinare cucinare HSK - tratti - 8 RADICALe - 火 Soffiare 吹 (chui fonetico) sul fuoco huo火 per mescolare e iniziare la cottura.炊具 chuījù utensili da cucina.Altri post sui caratteri cinesi

Family of characters 欠 qian

欠 qiàn – yawn; owe/ short of, lacking. The upper part evolved from the pictogram of an open mouth. A person人with an open mouth is yawning, or trying to compensate for the lack of air. 欠缺 qiànquē – lack/ be deficient of (lack + lack) 欠债 qiànzhài – owe a debt...

Una sesión de exorcismo taoísta

“Mi amigo va a concluir un servicio de exorcismo esta mañana y, si realmente estás tan interesado, espera que puedas venir y presenciarlo." Se detuvo inseguro. “Pero debo advertirte que no es una vista bonita. Realmente es muy desagradable, asquerosa y repugnante.”...